Check for infectious diseases

hy did California and Nevada mandate stay-at-home orders, but neighboring Utah and Wyoming did not? Why did the president of the United States tell Americans that COVID “will go away. stay calm. Will it go out ‘as hospitals are fully licensed and nurses and essential workers show up outside for protective equipment like face masks? Do we need to use an anti-virus to clean our messages? Can I see my neighbor if we are outside and socially distant? Where can I buy toilet paper? Should I wear a mask outside? Are we moving the part? How much time should we spend at home working while taking care of our children and online school? Do you think we should cancel our summer vacation? Is the government doing everything it can to protect me, my family, and my country? These are the questions we, like all Americans, began to ask ourselves in March 2020. As much of America’s economy and society has moved online and at home, we have seen our lives turn upside down from due to bad disease.

As political scientists, we are particularly familiar with the politics of change. And as scholars of political process and behavior – both in the United States and around the world – we pay attention to political history and how our fellow Americans react to it. Despite suggestions that it will ‘go away’, the first reports of rising case numbers, overcrowded hospitals, isolated citizens and lockdowns from China and Italy cannot be ignored.

Realizing the impossibility of the arrival of COVID-19 in the United States, we decided to use our skills to study American attitudes and behaviors. Each of us is an expert in a different policy area: emotional and external threats of terrorism and health problems, mainly in the United States (Gadarian); citizenship and democratic threats, including immigration and electoral interference, are central to Europe (Goodman); and the economic crisis and the decline of democracy, mainly in Asia (Pepinsky).

Our interest in existentialism began to flow into the same conversation. We want to know who in America shares our concerns. We want to know if the American people will come together to fight this challenge, or if, as we fear and suspect after years of research, politics will dominate America’s response. And we understand that we can give an idea of emerging problems that do not come from the echo chamber of social media or the cacophony of cable news.

Developing a large-scale research project to survey Americans about their attitudes and behaviors in response to emerging health problems is no small task. Social scientists at federal universities receive funding that differs from researchers and think tanks at polling agencies and that our research plans must be approved by an ethics board. In addition, academic researchers must receive their own funding and have an agreement with the polling agency to compile the questionnaire. This research will go out in the field, that is to our respondents. We did all this in the first two weeks of March 2020. We even wrote down our expectations in terms of what we thought we could find – in particular, that we would see differences in behavior and behavior related to COVID-19 – and shared them in the public archive. In the social sciences, this is called “pre-registration” of our research and analysis and is used to increase trust and reduce bias. With support from our ethics committee and emergency funding from the National Science Foundation under a rapid response research grant, our first study of Americans began on March 20 while we ourselves continue to work from home and that our children have started studying at a distance.

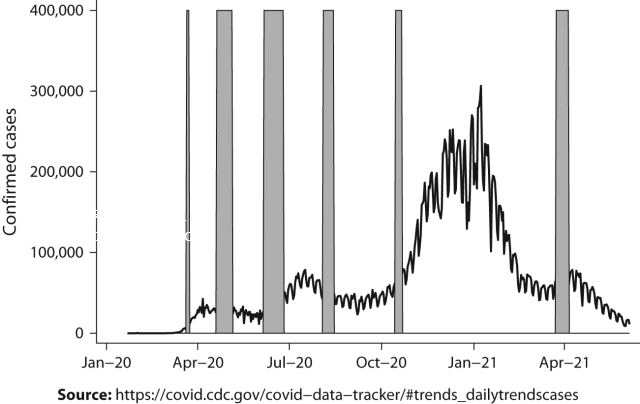

In total, we polled Americans every day six times, from March 2020 (as states began to shut down, schools went virtual, and many events were canceled) to March/April 2021 (after the inauguration of the President Joe Biden and on the recovery side of COVID. vaccine). Each wave gives us a different picture of America as the epidemic waxed and waned (see figure I.1). We can also tap into other programs that attract American audiences throughout the year. Six mental health tips for Indian millennials that really work

Questions can be asked about, for example, racial justice following the killing of George Floyd (wave 3), the challenge of opening schools (wave 4), the issue of another presidential election (wave 5) and attitudes towards vaccines (wave 6). ). An intelligent reader may look at this figure and ask why we didn’t do field research on an epidemic scale. For us, the worst time is to take the attitude before the election (wave 5) and after the dedication (wave 6) to see if the change of the part and power.

At their core, our polls are similar to public opinion polls published as part of the electoral process. They are designed to be nationally representative, which means that the respondents are chosen randomly, but in a way that makes them more or less representative of all American adults. This is important: because our respondents are a representative sample of all Americans, we can use our research to find out what Americans as a whole are thinking during this pandemic. The idea that a survey sample can be representative of the larger population is the foundation of public opinion research, and we adhere to this idea 카지노사이트.

That said, our survey differs from standard polls in two notable ways. First of all, they are larger than the standard sample: we started with three thousand people who responded to the survey in March 2020, about three times as many respondents as we see in many polls. This gives us much of what statisticians call “statistical power,” the ability to distinguish between groups of Americans with great precision. Small-scale research can help us understand all Americans, but it may not be possible to determine how small groups of Americans differ, for example, how attitudes may differ by income, race, and it is religion. To examine the complexities of Americans’ policy response to COVID-19, we need to collect data on more Americans.

Second, unlike standard polling surveys, our research follows the groups over time. This is called panel analysis. Public opinion research firms usually draw a sample of, say, 1,000 Americans to vote, then when they want to do another poll, they draw a new sample of 1,000 Americans. Our plan is to contact those we interviewed in the first round each time we conduct a new survey. In this book, we call each research process a wave of research, and our respondents are the ones we ask the most often who answer our questions. Tracking the same groups in a panel survey is more expensive and time-consuming than taking a new sample for each wave, because the research company has to call the same groups back and encourage participation.

However, this strategy gives us unprecedented insight into things like the strength or variability of beliefs and the impact of conditions (for example, the number of local COVID cases) or conditions (for example , becoming unemployed) over time. In the final wave of the survey in March/April 2021 (supported by a grant from the Russell Sage Foundation), we added a so-called “excess” item in which we interviewed non-resident respondents. white outside our panel, including 450 Black, 450 Asian American and 450 Hispanic respondents. Other respondents allow us to better understand how small communities have fared during this pandemic and their experiences with vaccines.