HIV clinical research talk is part of the return of the Global Health Politics Workshop.

The phrase “the path to hell is paved with good intentions” was used by Ann Swidler, a sociology professor at the University of California-Berkeley Graduate School, to headline her lecture on serious misconceptions surrounding global health challenges.

Swidler’s talk, “Paved with Good Intentions: Global Health Policy & Dilemmas of Care in High Viral Load HIV Clinics in Malawi,” opened the Spring 2023 session of the Boston University Pardee School of Global Studies’ Global Health Politics Workshop on Monday, Jan. 30.

Despite the fact that her research is scientific in nature, Swidler said that she had no prior experience in global health. She self-identified as a “sociologist of culture” and said that because of her sociological training, she is able to “find things that other people weren’t looking for.” The biggest difference, according to her, is between what “global actors” think life is like in Africa and what it actually is there.

Swidler argued that trying to 카지노사이트 change the lives of individuals you’ve never taken the time to comprehend is morally repugnant and unwise.

Swidler claimed that her research was motivated by her curiosity regarding how institutions’ levels of efficacy differ around the world. She added that she has devoted over two decades to HIV research in sub-Saharan Africa due to her specific interest in the ineffectiveness of HIV and AIDS medicines un African settings.

According to the World Health Organization, HIV impairs the body’s defenses against infection. Untreated HIV can develop into AIDS, making the infected individual vulnerable to a variety of other serious illnesses. According to WHO estimates, there were around 990,000 HIV-positive persons living in Mali as of 2021.

Nicolette Manglos-Weber, an assistant professor of religion and society at Boston University’s School of Theology, recalled collaborating closely with Swidler on a 2006 research on HIV transmission, prevention, treatment, and attitudes among Malawians. HIV has been referred to as a disease of poverty, according to Manglos-Weber. With the proper financial and social assistance, the illness is fairly curable and treatable. Antiretroviral medication, which maintains the immune system, lowers mortality, and improves quality of life for infected people, is commonly used to treat HIV infections, according to WHO.

However, the situation is different in Malawi. In 2019, Swidler and her team researchers spent the summer attempting to discover why the nation’s clinics were not effectively treating acute cases of HIV, as she claimed. “A really beautiful analysis of what the difficulties are,” which Swidler delivered at the workshop, was the result of the research, which also included field notes, observations, and interviews.

The Global Health Politics Workshop was started by Joseph Harris, an associate professor of sociology at BU, with the intention of raising awareness of the problems facing the organization and provide a forum for researchers and practitioners to exchange ideas.

“If the solutions to global health issues aren’t put into action or considered in relation to issues in the real world, Harris said, “often, they can just sit on a shelf somewhere and collect dust.”

The Pardee School of Global Studies website states that the lectures in the series will continue throughout the spring and focus on the following issue: “How can the study of the politics of global health crises assist to improving the state of humanity and assuring a brighter future?”

Swidler’s talk, according to Harris, serves as an example of “how and why politics are vital in understanding and explaining and, eventually, addressing the world’s various issues.” Swidler also emphasized how crucial it is to devote time, money, and knowledge to global public health research.

She said that “(global health research) has greatly enhanced life expectancy, virtually eradicated polio, and reduced newborn mortality as well as virtually eliminated river blindness.” “The advancements in global public health are just amazing.”

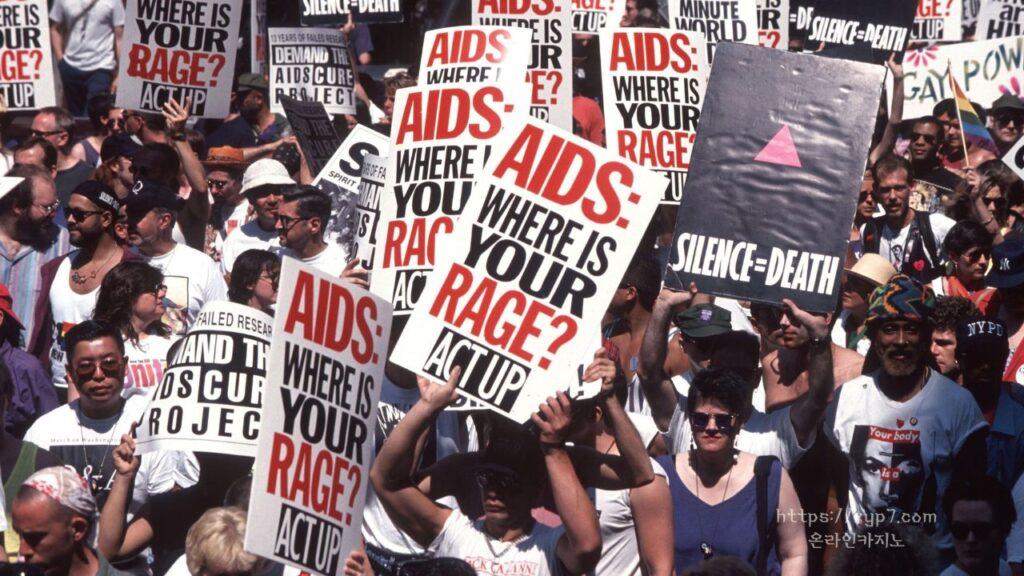

The employment of criminal and associated laws against people who are HIV-positive is referred to as “HIV criminalisation.” In various countries around the world, it is currently illegal to transmit HIV, expose someone to HIV, or simply fail to reveal one’s HIV status. In certain regions, HIV has been added to the list of communicable diseases that are already banned, while in others, specific legislation has been enacted.

Despite being inefficient, discriminatory, and a serious obstacle to HIV prevention, treatment, and care, the number of these laws (and their use) is rising. Laws frequently ignore the fact that HIV is no longer a death sentence, that good treatment eradicates the risk of transmission (U=U), and that the likelihood of HIV transmission from a single act of exposure is incredibly low, treatment or no treatment.

Making the distinction between intentional (planned) acts and unintended acts is crucial. The majority of HIV criminalization cases around the world feature harsh penalties for “reckless” or inadvertent HIV exposure or transmission. One of the most forward-thinking nations in the world when it comes to HIV criminalization is the Netherlands, which only criminalizes purposeful HIV exposure or transmission.

Unquestionably, it is illegal to intentionally and actively transmit HIV to someone in order to harm them. Both intentional HIV transmission and medical malpractice by healthcare professionals are extremely rare occurrences. Such situations can be tried under current law, making the need for additional HIV-specific legislation unnecessary. Because of this, South Africa decided not to pass an HIV-specific law in 2001.

The HIV Justice Network’s most recent global audit revealed that there are HIV-related criminal statutes in 75 different nations. Three regions of the world, including the United States, eastern Europe/central Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa, have a disproportionately high concentration of HIV-specific laws.

Since the United States became the first nation in the world to enact HIV-specific criminal statutes in 1987, there have been thousands of cases that have been documented. More than half of the states (27), albeit several, like California, Colorado, Iowa, Michigan, and North Carolina have modernized these laws, make it a crime to have HIV.

The eastern European and central Asian region presently has the second-highest number of laws that specifically criminalize HIV as a result of the adoption of such legislation in the second half of the 1990s. With a very high number of recorded cases and some of the worst HIV criminalization laws in the world, Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus stand out. In Russia, it is illegal to do anything that might expose someone else to an infection. Similar laws apply in Ukraine: you must disclose your HIV status before engaging in any activity that carries a risk of infection, and even in the absence of an HIV-positive diagnosis, “risky” behavior (such as injecting drugs) may subject you to criminal prosecution. An effective advocacy campaign in 2018 resulted in a law amendment in

Although there are significantly fewer reported cases of HIV infection there than there are infected people, the majority of HIV criminalization laws exist in the countries of Sub-Saharan Africa. Women are generally the first in a relationship to learn their HIV status as a result of antenatal HIV testing, just as they are in eastern Europe and central Asia, rendering them more susceptible to legal action than men.

In other instances, women have also been charged with purposefully exposing their own or another person’s child to HIV through breastfeeding. In the middle of the 2000s, numerous nations, notably in west and central Africa, enacted very comprehensive HIV-specific legislation. Since then, a number of nations have decriminalized vertical transmission and restricted criminal liability to acts posing a sizable risk of transmission in awareness of the harm these laws cause to the battle against HIV. Due to community advocacy, the Democratic Republic of the Congo completely abolished its HIV-specific statute in 2018. Zimbabwe recently moved to remove its HIV-specific laws, and Kenya is still working to have its HIV-specific criminal statute declared unconstitutional.